Introduction

Today I want to share with you some elements of the process of developing an animation, which I am doing with the skills and input of an animator. The animated film draws on my own experience of getting ill with hepatitis C and the impact this had as I struggled to cope and live through this unwelcome experience. As a social researcher with an interest in health, wellbeing, disability and marginalised identities, the insight gained through getting ill with a stigmatised and poorly understood condition has motivated me to tell others what it was like. The animation and associated material, such as this presentation, portray the domino effect that can occur when people become ill. Loss of earnings and a punitive benefits system have long-term repercussions that not only impact the individual but also their families and dependents.

Creative process

The creative process that I am a part of entails a weaving together of research practices, such as choosing what to include and what to leave out, and how to represent the story coherently without making it overly detailed. This is a similar process to the way research is analysed and written-up, making editorial and ethical decisions. However, what has been different with this process is that painful memories have been revisited because it has been my own lived experience that is the focus this time and this has shaped my approach. For example, we have decided to create a fictional setting and protagonist, Jane, as a way of visiting the key points of my own experience whilst also having some differences. This gives me a sense of distance, but highlights key points such as issues regarding health and social care provision, and the debilitating impact that poor health can have.

Empathy

When the film is completed, I hope that it will reach a varied audience. I want it to be a means of engendering empathy and understanding, helping clinicians, academics, policy makers and the public understand the patients’ experience in a more holistic setting. It has been noted that a key task in the training of medical students is to build empathy for their patients:

… the “cleanly mechanistic view” that science attempts to impose on suffering actually runs the risk of reducing the patient to a disease, an object, a practice that enhances controllability and safety but reduces empathy.

(Shapiro, 2008)

As a counter to the tendency for patients to be understood primarily through their disease and the quantified status of their test results and clinical observations, this animation is a very human portrayal where we demonstrate the life lived beyond the clinical encounter.

Ethics

As we have developed the screenplay, I have had to make ethical, creative, personal and professional decisions; for example, we had to decide how to portray the means of transmission which, for me is uncertain and likely to remain so. I wanted to be careful not to suggest blame of myself or others in how the transmission is depicted, yet I’ve wanted to make the point that bad things can happen, and that this can seem unfair and arbitrary. Unexpected events can take away the life you knew and the future you hoped for, and the network of support that one may have assumed was there to help individuals, turns out to be less robust than expected. I must add that I greatly value the NHS and its founding principles, but for me and others like me, health and social support mechanisms are not always sufficiently responsive.

This can have devastating effects that leave the most vulnerable in serious financial and physical circumstances, if you have limited resources, the holes in the safety net are too wide and you can fall through them. Some of these issues are explored in the animation through the experiences of the protagonist Jane, who, like me, becomes ill and doesn’t know what is wrong with her, she loses energy, loses hope, loses her house, fails to get PIP, and only finds out it is Hep C through a text from a friend. Jane is not an obvious candidate for Hep C, which tends to be associated with needle sharing, and both she and I go under the radar for screening. This raises issues around testing for the virus and the possibility that I could have gone for many years before finally being diagnosed, which increases the likelihood of liver cirrhosis. I was fortunate in that the new life-saving anti-virals came along in my lifetime, however, I was not eligible for them due to their cost which was over £40,000 at the time and I joined a Buyer’s Club as a means to legally import the drugs from India at a much reduced cost. Hence, this expansive project I am undertaking touches on issues relating to screening for Hep C, the stigma of living with a condition associated with drug use, issues around the limitations of health and social care provision, and, for me, embracing a new way of exploring and representing these issues.

Attrition

When I first started to think through how I wanted to talk about and share my own experience, the most obvious approach would have been to write a paper, but I was hesitant, it just didn’t seem enough. Words alone were not adequate for an experience that impacted in so many ways on both the inner and outer realms of my life. For example, my access to the material resources that could have helped me were restricted due to policy and budgeting decisions, and this then combined with my diminishing health, resulting in the gradual but steady attrition of my emotional and physical resilience.

Graphic Medicine

Through this collaborative partnership with the animator I am able to engage imaginatively and intellectually with this process. Animation and other methods of storytelling can engender understanding and comprehension, telling the audience, ‘this is what it was like for me and this is how I felt when it happened’. My work is finding a great match with the developing field of Graphic Medicine, which explores health and illness through graphic novels and comics. I am inspired by this form of representation and its associated theory, it is a way of thinking and showing, charting an alternate path through the research process. Although it is very new for me, what it is achieving is the creation of an expressive space within which I can examine the illness experience, what it means to me, and what it can tell us. As Susan Squier (2008) notes, with reference to comics and graphic novels:

In their attention to human embodiment, and their combination of both words and gestures, comics can reveal unvoiced relationships, unarticulated emotions, unspoken possibilities, and even unacknowledged alternative perspectives.

Subconscious

This is true also for this project; as I have noted, it didn’t seem adequate to write a paper, and animation allows for an inclusive means of exploring this issue and the topics that satellite out from it. Hence, for me, this is a type of philosophical inquiry, it is a making strange of something that was familiar (Malpas, 2014) and a making familiar of something that was strange. Animation is providing a medium for depicting the subconscious realm and the hidden world of the patient, one that can go unspoken and unremarked.

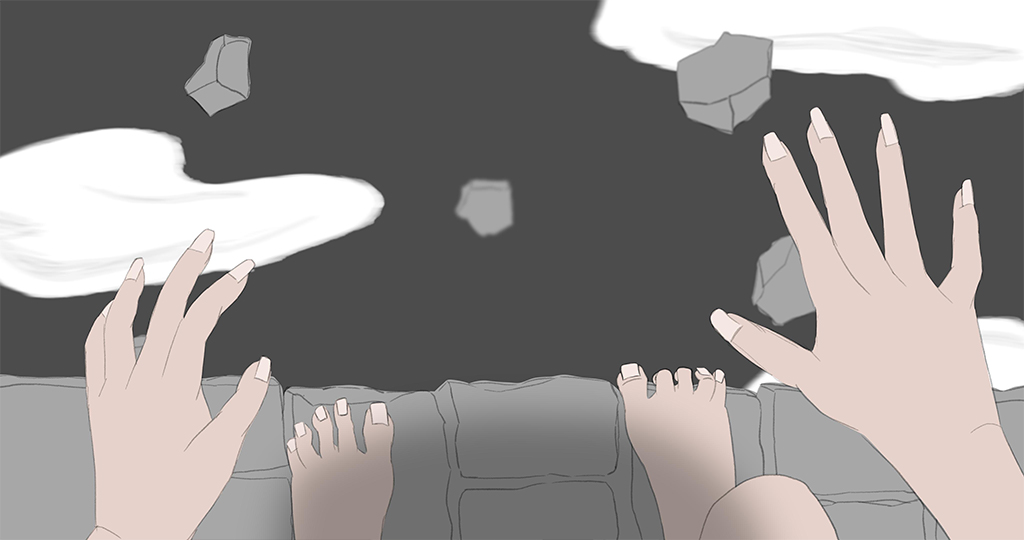

For example, I had repeating, symbolic and vivid dreams and night terrors when I was at my most ill, these fragments of my inner life went unremarked in medical encounters, yet they were woven through my waking life as a part of the reality of my experience and how it really felt. Now, I get to depict this sub-conscious, sub-language reality, as seen here.

Narrative

I also get to portray the importance of music and friendship, elements that enrich and give meaning to many people’s lives, helping us cope with the challenges encountered. These factors are now more broadly recognised in caring practices through, for example, social prescribing such as joining a choir or a gardening group. These elements are woven into the animation and remind us that health and wellbeing are expressed through and experienced in a breadth of factors that together help us live a good life. References to these factors are depicted in the animation, demonstrating with few words how Jane interacts with her surroundings. As Malpas (2014) notes:

Animation belongs to the very structure of the everyday… providing a means to see into and explore the reality of that world, and the possibilities it contains.

Certainly, what animation is offering me is the opportunity to adopt a holistic means of telling this story, it gives me the scope to define the dimensions of the world portrayed, and to set the parameters of how much I say. It could be argued that this artistic licence causes such work to be unreliable, yet research is often dependent upon what we chose to include and what we leave out as we synthesise and present our findings. In some sense we are all authors, editors and narrators in our research practice – in the stories we chose to tell.

Communicable disease

I wanted to depict the sense of paranoia and the awareness of the body’s permeability that accompanies having a communicable disease. Usually, when we cut ourselves, when we visit the dentist, or when we have blood taken at the hospital, our concern is for our own wellbeing, ‘I hope it doesn’t hurt’. However, for me, the concern was how to contain the virus and guard others from harm, for example, I faced the agony of having to tell close family and former partners that they needed to get tested as a precaution. This sense of contagion is something we refer to in the closing scene when Jane cuts herself, even though she is cured, worry and doubt remain. For the sake of completion, the story ends reasonably neatly with the closing scene depicting Jane dancing at a music event, her concern about cutting her hand on her way to the concert is a nod to the fact that life may not return to a pre-illness state. Instead, a new way of living must be forged.

Conclusion

We are seeking to share the film, when completed, as widely as possible, and at this point we will lose the authorial control we currently have, as people – the audience – can and will interpret it through their own lens, drawing meaning from it according to their own perspective and experience. My hope is that it will resonate with those who have faced various types of loss and trauma and that it may in some small way influence health and social care policy and practice.

Updates on the progress of the animation can be seen on my website, and if anyone is interested in disseminating the film when it is completed then do please share your details with me as we wish the film to be freely available.