Introduction

I am a social researcher who uses qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups to explore people’s perspectives and experiences. I’ve mostly shared my work through the written word, in scholarly articles that are quite densely worded and are often behind a paywall. This means that much research remains within the confines of academia and policy documents, limiting opportunities for people to access and engage with research findings. Therefore, I have been working with creative people, including an animator and musician, to produce short animations and imagery that bring my research to life through the blending of visuals, sound design, and narrative as a form of storytelling.

Storytelling is a part of our tradition, and it is something most of us are familiar with through literature, films, documentaries, TV series, podcasts, games, and audio books, among many other formats. Animation can explore and portray complex layers of information through images and sound, to convey feelings such as fear, doubt, hope and loss, helping the viewer understand things from another’s perspective, and nurturing compassion through that understanding.

Combining and showing research in different ways helps bring to life the insights I want to share, which are a mix of lived experiences, my thoughts, and my theorising and sense-making of them. Using sound, colour, visual metaphors and lighting act at a non-verbal level to invoke mood and to suggest to the viewer how the protagonist is feeling.

Steps

I have been using hand drawn animated films to share my research and will explain some of the processes that are involved, focusing on the screenwriting, concept design, animation, and music.

Screenplay

In our film In Spate, we tell the story of a woman who gets ill with hepatitis C, based on my own lived experience of the disease, we wanted the film to tackle stigma and to portray the often-hidden world of illness. We aim to show how illness impacts one person’s life, it isn’t a factual representation, it’s a mix of some real-life experiences but in a fictionalised form, and it is used to ‘evoke, rather than represent’ (Honess Roe, 2011).

The animator wrote the screenplay based on my notes and memories, in which I detailed key events such as being diagnosed and how I felt at the time, and any other details that helped tell the story. This took time, as I gradually recalled the timeline of events and the impact they had on me. Some of these details were then used to guide the writing of a fictional version, with fictionalised characters, this was done to protect privacy. It took several rewrites to develop the screenplay and to get the dialogue and action to a point where there was a version of the story that worked and was coherent. As we made decisions about the story, the main characters were developed, two women: Jane, the protagonist who becomes ill, and her loyal friend Moona.

In and On their Own Terms was based on an academic paper I wrote after interviewing severely disabled young people who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a muscle-wasting condition. The young people had explained how they experience disablist attitudes in their lives and how they did not like being patronised and talked down to, they also spoke about how they enact independence. I thought it would make an interesting short film that was accessible to a broad audience including young people. Decisions were made about what information and action to put in and what to leave out, and how to remain faithful to what the participants had said, while using fictional devices to carry the narrative. One character, ‘Ollie’ was created who would act as a narrator for all the participants I had interviewed.

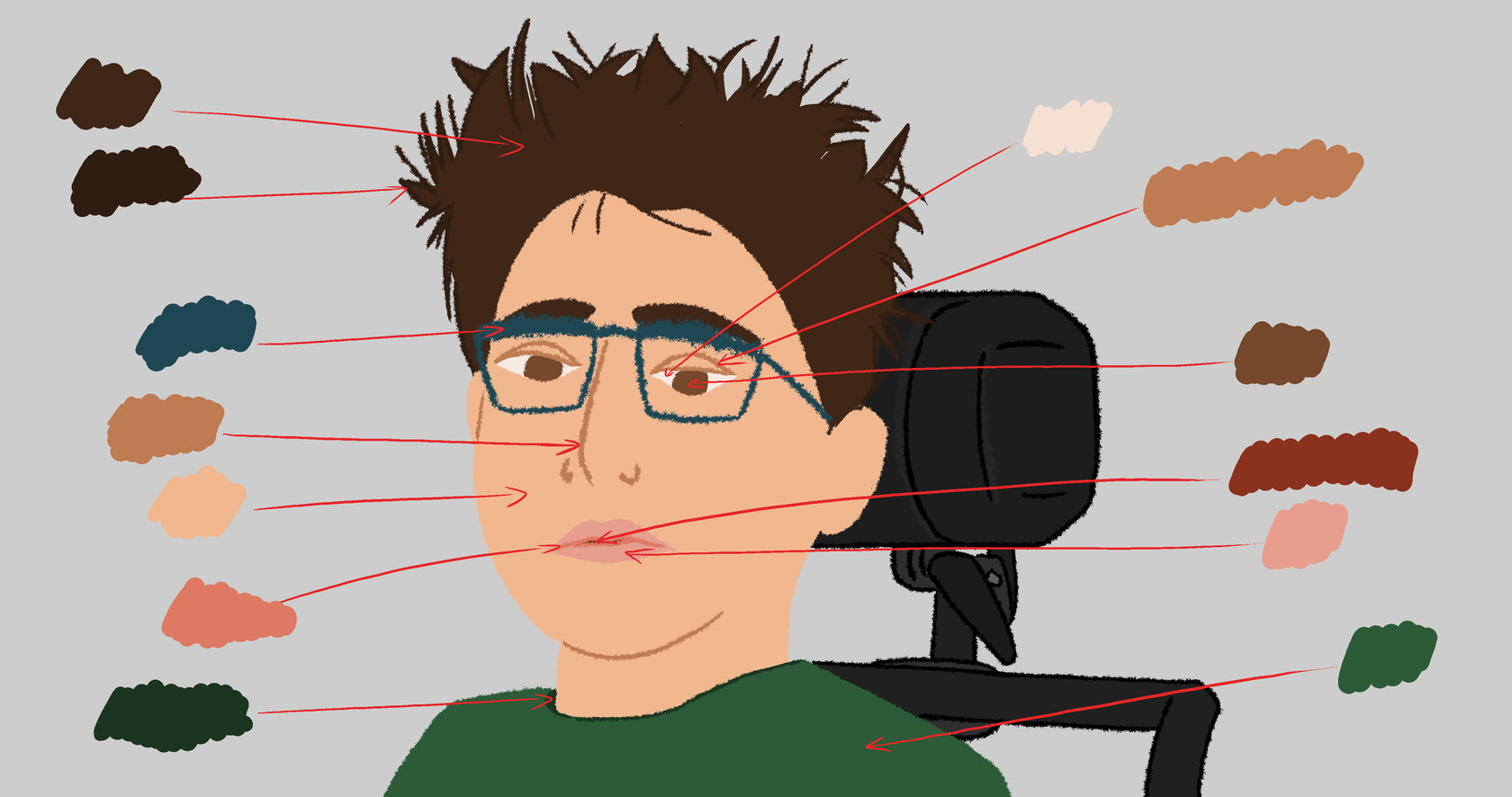

Concept design

In the film In Spate, we wanted the backdrop for the story to be Northern England, and we produced external sets for where the action would happen and also designed the interior settings; choices had to be made about rooms, furniture, and the mood and lighting for each scene. It took several iterations to find characters and backdrops that we were happy with, and some ideas for storylines were ultimately rejected as the story evolved; I wanted to convey the losses that are associated with serious illness without being overly detailed or too dramatic.

The film Seeing the Patient, is a short animation that we created to accompany a blog I wrote for the Shame and Medicine project which is based at Exeter University, Wary and watchful: Life with hepatitis C, we used a visually less detailed format, partly for funding and time reasons, but also as I wanted to explore inner feelings such as fear and anxiety, and we created tension through the use of a contrasted colour palette when the patient is afraid and wants to escape the clinical setting.

Animation

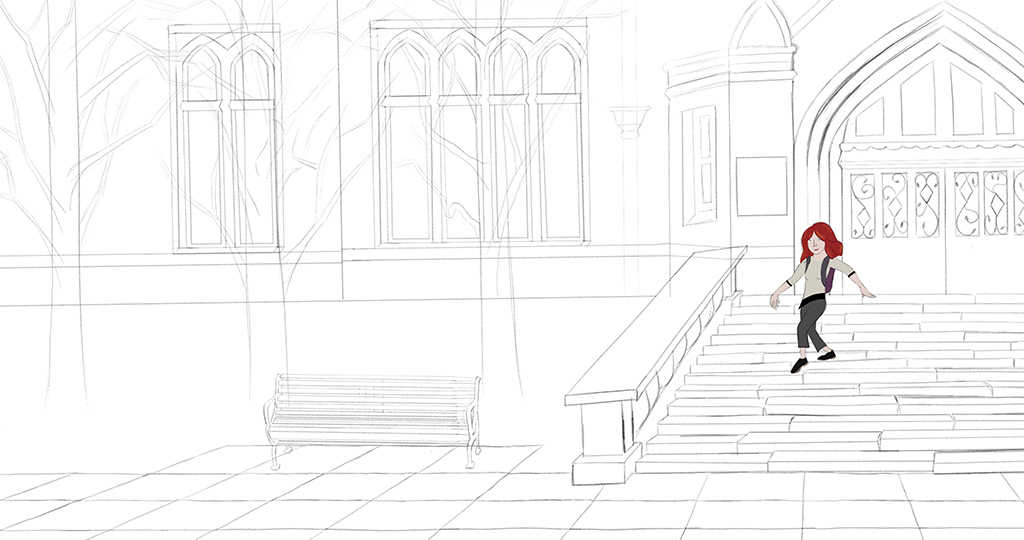

For In and On Their Own Terms we first did an animatic, which is a series of rough drawings that give an idea of the actions and timing of the film. We then add a temporary voice over and sounds. At this point any errors in how the piece works as a whole, such as dialogue that seems ‘clunky’, and any incoherence in the story will become apparent. Because these are rough drawings, changes can be made in a timely way, which is much less onerous than if it was the final animation. Indeed, for this film we have a total of 12 frames per seconds, and so for a 2.30 minute film there are thousands of frames that the animator has to draw and colour.

Once I was happy with the overall ‘look’ of the film, the animator produced a Previsualisation using 3D models, to help me see how the film would work in terms of the movement of the characters within the shots and with the camera placement, enabling me to think about how this helps portray the character’s perspectives and their physical location in each shot. A 3D environment allows us to act almost as if we were producing live action film; we don’t need to redraw the frame if we wish to change a camera angle in a scene; we simply move a virtual camera.

Once the actions and camera are agreed and ‘locked’, the animator can start the actual drawing of the animation. He’ll do a first rough pass, and as I confirm this is what I want, he’ll do a clean line version of the animation to finally colour the drawing; based on what was agreed in the concept design phase. It is a long process (it took more or less 9 months for this particular film) and much discussion between me and the animator to confirm that the illustrations fit with my vision for the film. This ongoing discussion is important as it avoids the animator creating unnecessary work, hence this is a collaborative process that takes several iterations. This is a time consuming and tentative process, in which the creative vision is worked toward through a series of decision-making, while also going with your ‘gut feeling’ and sense of what the film should convey in its completed form. During the process it can be difficult to imagine the end of production, however, I am so pleased with the final film and this has brought such a feeling of satisfaction due to the combined efforts of our small team.

Sound design and music

In Seeing the patient I wanted to depict how patients with stigmatised conditions can feel shame and discomfort at health care appointments, and to graphically show the fear they can experience, and which can deter patients from attending appointments. The use of sound design, such as echoing footsteps and the swinging overhead light depict how when we are afraid, normal, everyday sights, smells and sounds become amplified, and we portray this through the sounds and imagery. The closing images show the patient relaxed and much less anxious as they talk with the clinician, and we use bird song to create a bright contrast with the earlier scenes of fear, worry and distorted sounds.

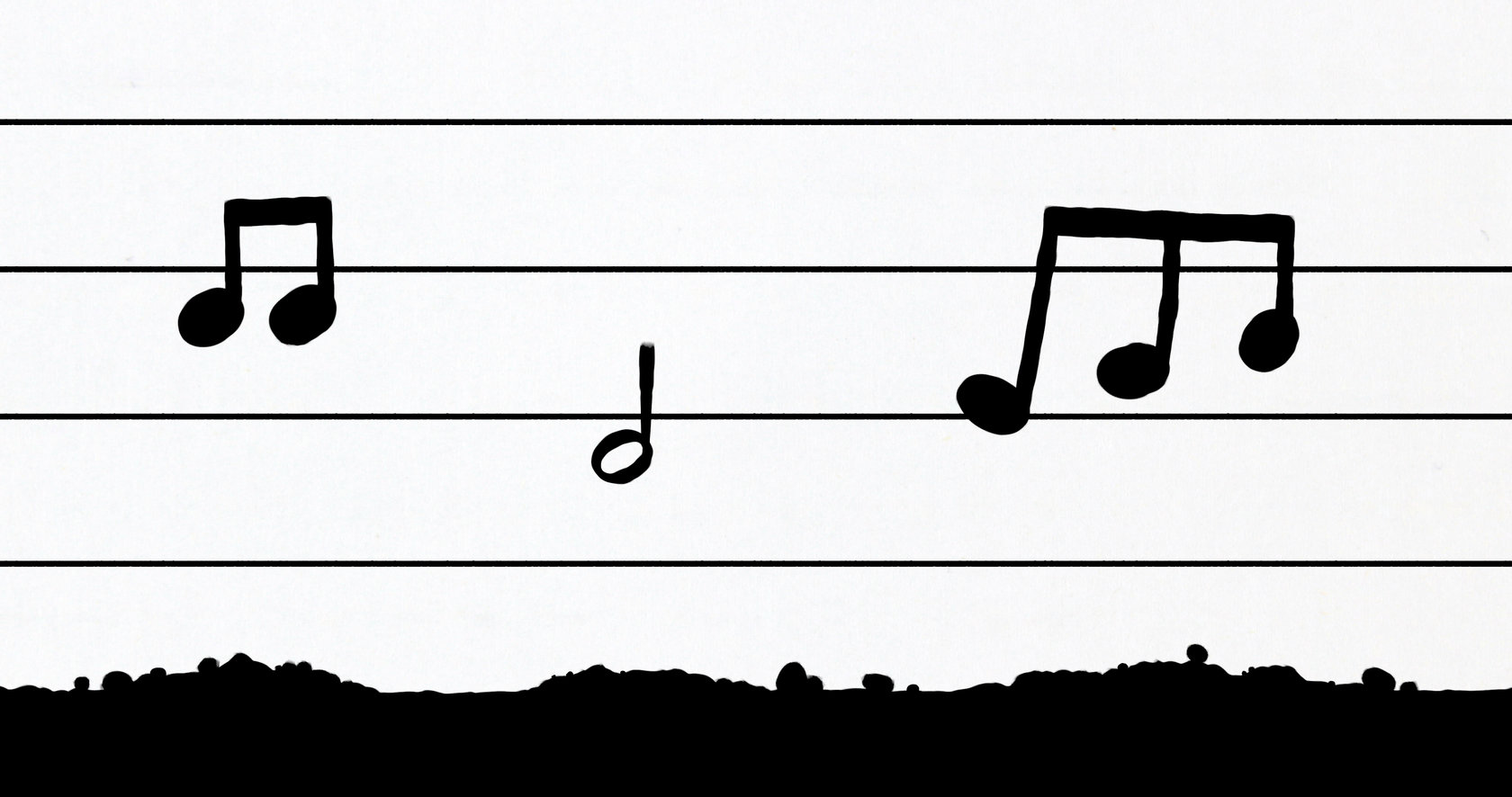

Music is another important part of the film. For In Spate I described the story to the musician and explained the overall feel I wanted from the music, I didn’t want music that was too emotive, it was essential that it can support the story without dominating it. He produced an initial version of the music, and I then gave feedback on what I thought was working and where I thought a slightly different approach might work. This is a challenging process, and I’m not a musician, so Wes was having to interpret what he thought might be effective, and what he thought I was trying to describe; fortunately, as he has composed for similar projects before, we were able to reach a place where a shared understanding developed, which resulted in the final music score. It brings the film to life, highlighting moments of doubt and loss, and depicting friendship and hope, the music acts as part of the non-verbal narrative of the story.

Conclusion

Arts and creativity can uncover new ways of looking at life, unlocking the inner world of thoughts and feelings, and helping us to think about and understand lives and experiences that may be invisible or poorly understood by others, such as those of severely disabled young people and of individuals who go through serious illness. The power of storytelling lies in its layered use of the non-verbal along with other means of telling, such as images and sound. Practitioners can work with diverse resources to tell stories, such as drama, music, photography, sculpture, embroidery, poetry and other types of creative expression, to help us make and convey meanings.

As the artists Grayson Peery notes, ‘art helps us access and express parts of ourselves that are often unavailable to other forms of human interaction. It flies below the radar, delivering nourishment for our soul and returning with stories from the unconscious’.