Introduction

I am currently developing an animated film, ‘In Spate’, based on the experience of getting ill with Hepatitis C, a virus that causes liver damage leading to a range of health issues and which, if untreated, can lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The virus is passed on by blood-to-blood contact, such as through a contaminated blood transfusion, unsterilised medical or tattooing equipment, and is frequently associated with drug use and needle-sharing. As a viral infection that has these associations, Hepatitis C is frequently stigmatised and people may opt not to disclose their diagnosis to others. Because I had been through this experience, I knew that I wanted to share it with others, but I felt that writing an academic journal article was insufficient, there were things that could not be expressed through words alone. I also wanted to reach out to a broader audience because as a researcher who already has an interest in health and social care issues, I have a dual positioning, and now know what health and social care looks and feel like from this perspective. Things that I was aware of, such as peoples’ struggles for financial support and prompt medical care became part of my lived reality and my growing awareness of the gaps in care. As this quote suggests:

Minority identities acquire the ability to make epistemological claims about the society in which they hold liminal positions, owing precisely to their liminality.

(Siebers in Davis, 2013)

It is disorienting and hard to cope when a health crisis occurs, particularly if you frequently feel unwell, and there was a domino effect, with other areas of my life seeming to shift and become unstable. This sense of being overwhelmed led to us coming up with the title ‘In Spate’ for our film; the dictionary definition for spate is of a flood, an inundation, turbulent water characteristic of a river in flood. A large series or sudden excessive amount of words, events. This describes well both how one can feel to be physically flooded by the virus, and also how one’s life is likewise flooded by overwhelming events. Hepatitis C has been called a silent epidemic as the disease has a diffuse range of symptoms including digestive issues, joint pain, fatigue and itchy skin that can be mistaken for other conditions. The clinician James Freeman is an advocate for patients with Hepatitis C, and he has stated that ‘Hep C has no funding because it has no voice, getting patients to speak to (and for) it is vital’.

The Project

Bearing in mind these issues, and drawing from my own lived experience of how these matters intersected in my life, I am working with an animator to develop a short-animated film. We are funded by the Tilly Hale Award from the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Newcastle University; the award is for patient and public involvement activities. We have created a protagonist, Jane, who goes through some of the same experiences I did, but is also sufficiently different that there is no direct comparison. We chose to depict her as working in a fictional university and she may appear to have the social capital and associated resources required to cope reasonably well with adversity. Jane starts to feel unwell, with extreme fatigue, joint pain, brain fog and various other symptoms, but these are not sufficiently checked out by her GP and it is suggested that she has depression.

Eventually, she is diagnosed with Hepatitis C, but must then struggle on; it is increasingly difficult for her to cope and she feels very alone and increasingly scared and worried by what is happening to her. Her daytime anxieties continue into the night, and, just as I did, Jane has night terrors and recurring dreams. I never mentioned these to clinicians, it would have wasted the precious few minutes I had with them, where my focus was on staying as well as I could. Although I didn’t mention them at appointments, those dreams were embedded in the hinterland of my inner psyche and now we get to illustrate this dis-ease in short dream sequences, as Jane struggles with the encroaching sense of danger and threat. This sub-language level was an indivisible part of my lifeworld, yet it went unremarked, as Williams and Carel observe:

Within the biomedical practice, large differences exist between how practitioners think about disease and illness and how patients experience their illness

(Williams & Carel, in Aho K, ed. 2018)

Due to the current pandemic, it is likely that we are all now more aware of the turmoil viruses can cause, creating fear, uncertainty, and economic precarity. These are the issues Jane faces when she becomes too ill to work anymore, and she loses her house, and struggles financially as well as physically and emotionally. I know the demoralising experience of applying for benefits such as PIP, how much energy it takes to put in an application, and how crushing it is to be turned down, and the pressure that this places on patients to prove how ill they are is unjust. In my own life, the fact I am an academic and that I am able to express myself reasonably well made no difference, I know that in some cases social capital can help, but the rules I came up against were inflexible.

The Process

Until I started to work with the animator, Jeremy Richard, I had no knowledge or experience of working in a visual medium, my work was all in a written format and usually had quite tight, commissioned parameters and goals. So, it has been a whole new way of working and one of the things I now recognise was that as we began to work on the project, I was waiting for someone to validate what we were doing. I did get two Hepatitis C nurses to read the first version of our screenplay, just to make sure I had got some key points correct, but beyond that, I have had to take ownership of my role in the project. This means working without specified parameters, and it’s taken time to get to where I now feel more in control of the process as a co-author/director of what we are producing.

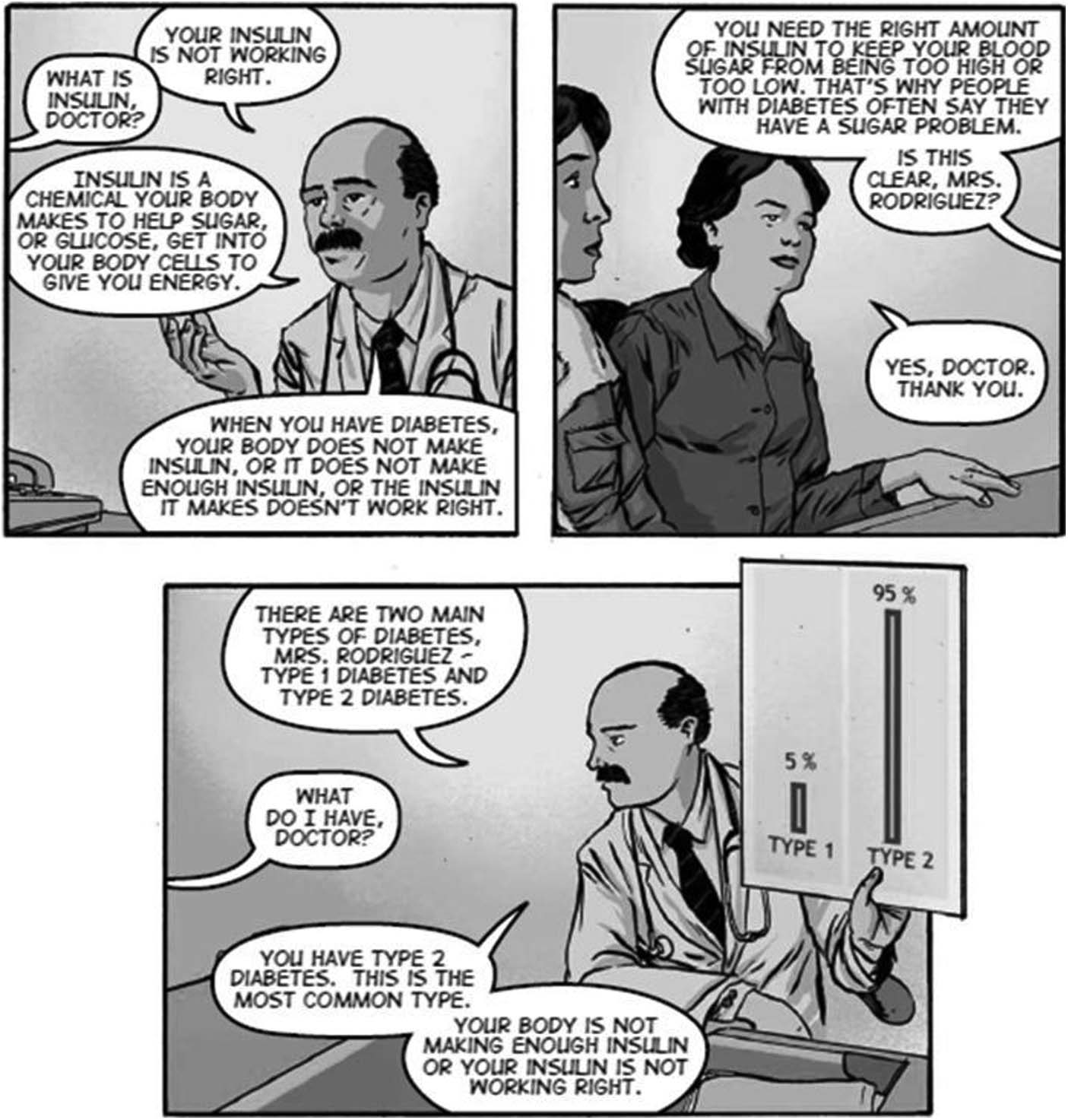

A source of theory and practice that has helped me make sense of this process has been the field of Graphic Medicine, which some of you may be familiar with. It explores health and illness through graphic novels and comics and combines imagery with words to represent the experiences of the patient, and in some cases the clinician. As Dr Ian Williams notes, with reference to graphic medicine and the role of comics:

Comics, like poetry, seem to allow more leeway in terms of meaning and, like film, offer the possibility of words juxtaposed with a contradictory image.

(Williams 2012, p25)

The creative process we are in is helping us find ways to represent loss and fear through the portrayal of an individual’s experiences so as to encourage empathy and understanding, and we are using story, image and sound design to achieve this. This further quote captures the process that animation is offering us:

Animation… is increasingly being used as a tool to evoke the experiential in the form of ideas, feelings and sensibilities. By visualizing these invisible aspects of life, often in an abstract or symbolic style, animation that functions in this evocative way allows us to imagine the world from someone else’s perspective.

(Honess Roe 2011, p227)

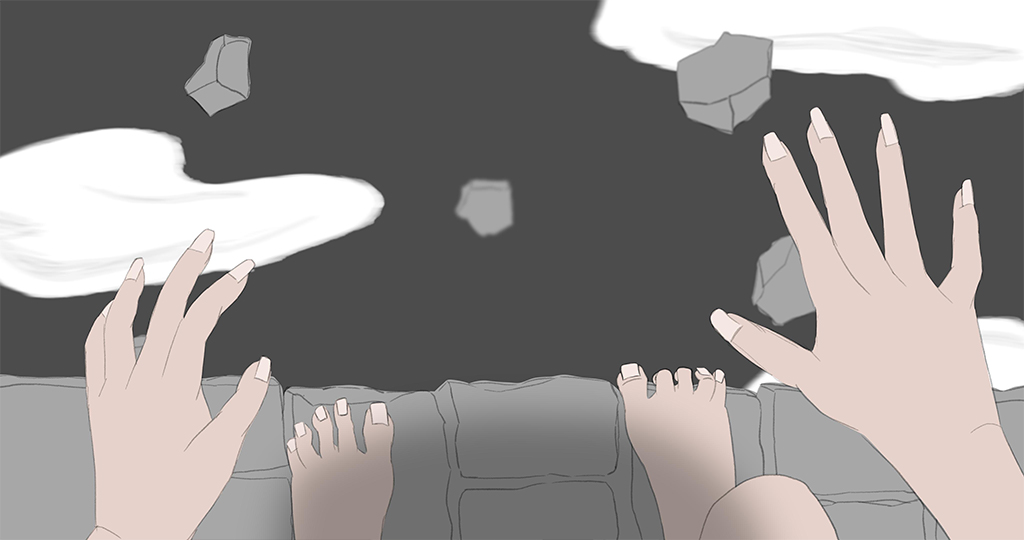

In my own life I felt to be on the edge of a precipice, this was intensified by the fact I also have an autoimmune condition, and I was often caught between two specialists who did not treat me holistically. It was an impossible situation and it felt like it was often just me and my GP that muddled through it.

The above visual Jeremy produced, that has not gone into the final version of the story, shows how it can feel. There were elements of my experience that I can only describe as hard to endure, a form of suffering, although I know this is a problematic word for some in disability studies. I felt myself to be between a rock and a hard place, unreachable, in pain, and really not doing well.

Buyers Club

At the time I was diagnosed, the only treatment for Hepatitis C was with Interferon, which is risky for patients with autoimmune conditions to take, I knew that clinical trials offered hope, but, like Jane and other patients, I had to be patient and wait. Eventually, in 2014, direct acting, and very well tolerated anti-virals were becoming available and news of their efficacy was promising and exciting. However, due to their cost, the drugs were being triaged in the UK, where the price was prohibitive unless you were wealthy:

The new drugs, in combination with older ones, can cure hepatitis C infection. But the cost of an eight-week course of one of them… sold by Gilead under the brand name Harvoni – costs £26,000 and a 12-week course is £39,000. That is before VAT… Some people may need a 24-week course, costing £78,000.

(The Guardian, 28/07/2016)

Jane has to find a way to gain access to the drugs, and just as I did, she joins a Buyer’s Club, which is a way to legally import the drugs for personal use from India where they are sold much more cheaply. This can feel like a risky process as the buyer is stepping outside of NHS care and shifting from being a patient, to being a consumer. However, the club I used was very helpful and supportive and the life-changing drugs rapidly began to work and, unlike people with HIV, after the course of drugs has been completed, no further dosing is required. Once she takes the drugs, Jane rapidly begins to feel better, and starts to engage with life once more.

Here we see Jane at the public library, catching up on some reading for an upcoming job interview, before going out for the evening with her close friend Moona, who has shown kindness and support to Jane through her darkest moments. As just mentioned, Jane has a job interview soon, she needs to find work so that she can once again support herself. The process of long-term illness and the accompanying physical and financial attrition are hard to recover from, and this hardship can have ongoing impacts. So, in this animation project, we want to reach the public, patients, and anyone who has encountered adversity and the accompanying domino effect that can occur. We also wish to reach researchers, policy makers and clinicians, and to develop compassion and understanding through depicting one woman’s experience.

It is at this point in Jane’s story that we leave her, the key points from her experiences have been illustrated, points that may resonate with others around issues such as struggling with unexplained symptoms, being taken seriously by the medical profession, getting a diagnosis, dealing with the stigma that accompanies some conditions, and the associated financial challenges that patients go through when they are ill. I would now like to share with you an excerpt from the upcoming film ‘In Spate’: